Neuroreality for pain management

By Alejandro Elorriaga Claraco

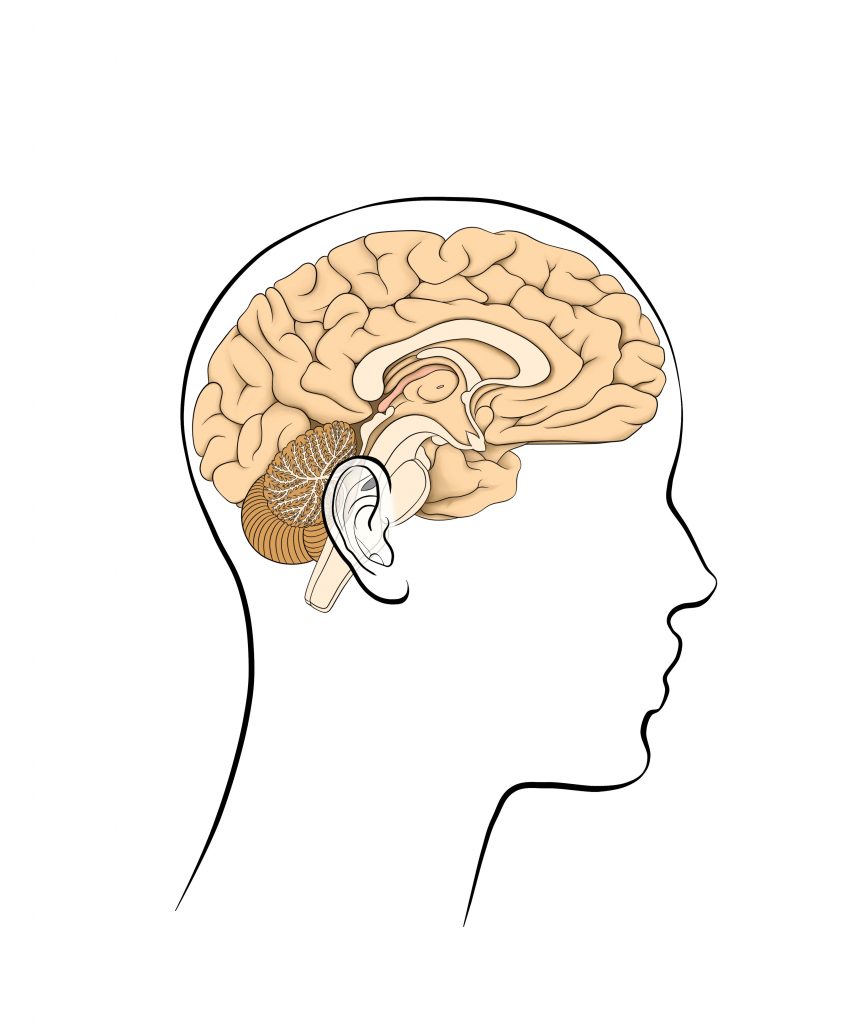

Features Clinical Techniques Limbic system: the neuroanatomical substrate of psychoemotional neuroreality

Limbic system: the neuroanatomical substrate of psychoemotional neuroreality Three centuries ago, in 1710, the Irish philosopher George Berkeley proposed this famous thought experiment: “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” He used this question to discuss his philosophy of “immaterialism,” which argued that perception creates reality and that nothing exists outside our minds.

His idea, “esse est percipi” (to be is to be perceived), surprisingly for its time, seems to be in full agreement with 21st century neurophysiology.

For scientists, the answer to Berkeley’s question obviously depends on the interpretation of the word “sound.” Scientifically, the origin of sound is a vibration that, through a complex set of physical and physiological events (mechanical, chemical and electrical), ultimately results in the stimulation of certain areas of our brains, producing a sensory experience that we identify as an acoustic perception, which we call “sound.” The fallen tree will certainly produce a certain vibration of the air, but in the absence of an auditory apparatus connected to a central nervous system there will be no sound or, more appropriately, there will be no sound perception.

Sign up to get the latest news and events from Canadian Chiropractor. Our E-newsletter will be sent to you only once per week, on Mondays.

Finally, 300 years later, with a straightforward neurofunctional logic Berkeley’s thought experiment seems to be elegantly solved – or not? Our new dilemma starts with the surprising corollary to our scientific solution, which reads, “If no one is around, it should not matter to anyone what happens when the tree falls.” To be clear, this is not an impertinent inference, but an accurate one from a neurofunctional standpoint. It means that, after all, the only experience of the world humans can ever have, are limited to the neuro-perceptions our brain creates in every occasion in response to the complex activation of diverse groups of peripheral and central neurons by internal and external stimuli.

Unique reality

There is no objective reality and it is the brain – our brain – that creates the only reality we have access to: our neurological reality, our unique experience of the world that is only available to each of us.

This neurofunctional concept will help us shed new light on the challenges we face every day in clinical practice when dealing with pain with movement disorders.

Let’s use again Berkeley’s experiment, but now in a new manner: “If a tree falls in a forest, what happens if several people are present?” Scientifically speaking, every person present – provided they have a functioning auditory apparatus and a brain – will certainly perceive a sound. However, this sound experience will be different and unique for each person, as a result of all having different brains.

Corollary, as we know, there are as many experiences of the world, as many realities as individuals in the planet. We should have a name for this neurofunctional phenomenon just described, a name that reconciles philosophy and physiology, and expresses the very nature of our experience of the world.

Although it has already been used elsewhere with a different meaning, the author proposes to use the term “neuroreality” to represent the concept of our unique experience of the world. In a neurofunctional context, neuroreality refers to the whole set of “experiential neuroperceptions” created by our brains throughout our lives, and perceived and interpreted by us as our own accurate experience of the world.

Not surprisingly, many contemporary models of brain function and consciousness have incorporated the concept of neuroreality, albeit using other terminology. For instance, Ronald Melzack’s neuromatrix theory in 1990 represents the “individual widespread neuronal activation associated to every pain experience, acute or chronic.”

The concept of neuroreality presented in this article extends beyond the experience of pain, and attempts to become the foundational neurofunctional principle that represents the nature of our rather deceiving relationship with the world. Whatever we perceive is real to us, pain and pleasure alike, regardless of other people’s own perceptions, opinions, beliefs or ideas.

Pain problem

Our individual neuroreality is built over a lifetime of conscious neuroperceptions generated by a myriad of external and internal stimuli, such as thoughts (personal or from others), emotions (pain, fear and pleasure mostly), and sensory perceptions (smell, touch, sound, sight, taste, temperature, vibration, etc.). The problem with the nature of neuroreality is that it conditions itself, i.e. it conditions the processing of new stimuli, giving every new experience or perception a biographical and cultural dimension, including the experience of pain.

The concept of neuroreality serves not only to validate Berkeley’s idea of a subjective universe but, at the same time and more importantly, it serves to liberate us from the tyranny of the structure that has dominated pain medicine for the most part of the history of medicine.

In a nutshell, over 2,500 years of philosophical adherence to a non-existent objective universe, plus the reductionist view of the human body as a mechanism – instead of a complex biological system with mechanical and other dimensions – have led medicine in general and pain medicine in particular to a linear (and often unidimensional) therapeutic approach, based on the principle of causality.

This approach has often led to the search of single causes and single interventions to treat pain problems. In this manner, particular structures have been signaled as the cause of specific pain problems, e.g. intervertebral discs, zygapophyseal joints, trochanteric bursae, subacromial or deltoid bursae, carpal tunnels/median nerves, thoracic outlets, sciatic nerves, plantar fasciae, iliotibial bands, and many others. The failure in resolving the pain problem when treating the offending structure, or worse, the existence of many people walking the streets with the same faulty structure but not symptoms, have not yet deterred main stream medicine from using this belief-based diagnostic system, where the structure is deemed to be the cause of the pain problem.

As we all know, ignoring the concept of neuroreality in general and the physiology of neurofunction in particular has produced less than exemplary results in the treatment of pain problems over the last several decades: the current horrendous opioid crisis, the multiplication of interventional pain clinics with poor effects on the number of chronic pain patients and their quality of life, the increasing performance of some ineffective surgeries that often generate more pain and dysfunction, and the widespread disempowerment of pain sufferers by “medicalizing” their problems and extricating the biographical and cultural dimensions of their pain experiences from the therapeutic approach.

If we, health-care professionals of the 21st century dealing with problems of pain with movement, embrace the concept of neuroreality, it will help change the current gold standard approach to the assessment and treatment of pain problems. A contemporary neurofunctional model, with a practical neurofunctional operating system, is needed for practitioners to be able to analyze pain problems as the neurological issues they really are, and to treat them not just as the result of structural failures, but as the result of a complex multidimensional system failed adaptations.

With such a neurofunctional approach, more effective therapeutic interventions will be generated to help the millions of sufferers of pain with movement disorders.

Albert Einstein once said, “Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one.” Like quantum reality, human neuroreality is also a mere illusion too, from an objective existence standpoint. The great news for humans is that, unlike in quantum physics, if we don’t like our neuroreality, we have the ability to change it for a better one. And that will be the topic of a series of follow-up articles on the neurofunctional operating system used by this author to assess and treat individuals suffering with pain with movement disorders.

It is a “treating beyond the structure” approach that produces remarkable results when neurofunction is improved and a new neuroreality ensues.

CLICK FOR PART TWO OF THIS SERIES

Dr. Alejandro Elorriaga Claraco, is an international sports medicine consultant who has worked with hundreds of professional athletes and thousands of clients for over three decades. He has used his extensive clinical experience and research to become an innovative educator in the field of “pain with movement” disorders. Find out more on www.mcmasteracupuncture.com.

Print this page