Our May column chronicling the exploits of Harry Yates, and his

record-setting 1919 London-Cairo flight, struck a chord with readers.

Here are a few of your comments:

Our May column chronicling the exploits of Harry Yates, and his record-setting 1919 London-Cairo flight, struck a chord with readers. Here are a few of your comments:

Dr. Craig Jacobs of Toronto remarked on the dangers of early flight and wondered how Col. T.E. Lawrence, the legendary Lawrence of Arabia, came to be stranded in an extinct Cretan volcano.

|

|

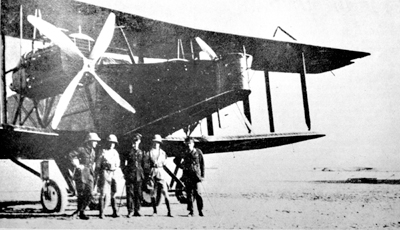

| The Handley Page bomber in Cairo. Harry Yates is first left, Harry St. John Philby is second from the right. The photograph was taken by T.E. Lawrence to mark the record flight.

|

A DANGEROUS BUSINESS

Flying was indeed a dangerous business in 1919. 2009 marks the 100-year anniversary of powered flight in Canada. Long distance flying was no cakewalk in the early 20th century, and it had only been 10 years since the Silver Dart hop-scotched its way into the history books across Cape Breton’s frozen Bras d’Or Lakes. So the prospect of young Harry Yates flying a British VIP across Europe to Egypt, and doing it in record-breaking time, did not augur well for the 22-year-old London, Ontario, native.

|

|

| Sub-Lieutenant Harry A. Yates. |

|

|

|

| CMCC governing board, 1946. Dr. Harry Yates is seated in the foreground; Dr. Joshua Haldeman is the tall figure standing to his right. |

Earlier that year, 51 Handley Page [HP] bombers left England for the Middle East to reinforce British foreign policy in the increasingly volatile region. Six months later, only 26 had arrived. The others were scattered across Europe, having crashed, or been otherwise disabled, and killing 11 airmen. Lawrence was counted among this group when his bomber crashed near Rome, killing both pilot and co-pilot, and immobilizing him with a broken collarbone and damaged ribs. Having convalesced for a time in a Roman hospital, Lawrence managed to continue as far as Crete, where he ran into Yates and Philby when Yates’s HP settled onto an airfield inside the crater of the extinct volcano. Yates had been charged with delivering Harry St. John Philby, a Foreign Office operative, to the Middle East to quell tensions arising from the British reneging on promises of Arab autonomy in exchange for their WWI military support against the Ottoman Turks. Luckily for Lawrence, the chance encounter allowed him to hitch a ride to Cairo, where he collected his notebooks to write Seven Pillars of Wisdom, an account of his involvement with the Arab revolt of 1916-1918.

Harry’s co-pilot and countryman, Jimmy “Buzz” Vance, went on to become a pioneer in Canadian civil aviation, and died in a crash on Great Bear Lake in 1930.1

COLOURFUL CHARACTERS

Part of the allure of the Yates story is the colourful subplot of characters associated with his record-shattering flight. Lawrence, famous in his own time, has since transcended into myth and legend. Recognized for his liaison role during the Arab revolt, and for his sympathies with Arab aspirations for independence – subsequently betrayed by the British – his legend has benefited from both movie treatment and a romanticized death at an early age. Philby, on the other hand, was one of history’s hard luck characters. Although he later became governor of Mesopotamia, and was one of the most influential persons in the modern history of the Middle East, he was overshadowed by the illustrious Lawrence in his own time and is chiefly now known as the father of the infamous Kim Philby, one of the most successful British/Soviet double agents of the 20th century. Philby Jr. was so effective as a spy for the Soviets that his activities were moderated only by Soviet fears that he was actually a triple agent.

Dr. Ken Goldie of Lumsden, Saskatchewan, noted that the tall figure standing behind Yates in the 1946 CMCC board photo was Dr. Joshua N. Haldeman, another adventurer and aviation enthusiast.

Serving on the governing board with Yates, Haldeman was also an avid flyer and, in 1954, flew 30,000 miles in a single-engine plane across Africa, Asia and then to Australia, perhaps the only private pilot to accomplish the feat.2 Haldeman spent years in search of the mythical “Lost City of the Kalahari” and was killed in an unrelated plane crash in South Africa in 1974. The quality of its first board members speaks volumes about the commitment and importance the chiropractic community put on its newly minted national school.

A RELATIVE UNKNOWN

Dr. Joel Weisberg of Toronto writes: “Given the magnitude of Yates’s achievement it is surprising he is not better known – why?”

Part of the reason is that the mission was secret at the time, but largely it was because of the dismissive attitude of the British establishment concerning the accomplishments of colonials. British servicemen routinely received advancement and honours ahead of their colonial counterparts for equal or lesser accomplishments. RAF Major A.S.C. MacLaren, an Englishman who set the original London-Cairo record, had been awarded an Air Force Cross (AFC) and bar for his achievement. Yates, who slashed Maclaren’s record by at least two-thirds, and did so with minimal ground support, sailed for home in 1919 without official recognition for his flight. Incensed, Yates’s father wrote then Canadian prime minister Robert Borden to intercede on his son’s behalf and ensure he received the recognition he deserved. With Borden’s support, Yates Sr. took the case to the Canadian High Commissioner in London. In the words of Guy Simser, author of the definitive account of Harry’s aviation exploits, “Testy letters were exchanged,” however, “a year and a half after, Yates Sr. pled the case, the two pilots were presented with the AFC.”3 This did little to lessen young Harry’s bitterness about his treatment in flying for the British. Earlier, in 1918, he had written home, “In the next war, there is one service I certainly will not be with and that’s the RAF.”4

The career of Dr. Harry Yates, DC, the chiropractic professional, remains to be documented. Simser used Yates’s diaries and the letters he wrote home to flesh out his account. These documents are in The National Archives of Canada, in Ottawa. Records associated with Yates’s tenure as a CMCC board member are preserved in the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College Archives. I would be more than happy to guide interested researchers through the records associated with CMCC’s early years, where documents associated with Yates are likely to be found.

You can also access records in the CMCC archives remotely by searching our new archives database via the web. Go to www.cmcc.ca >> Health Sciences Library>>Resources>>Archives Database. Select the “Search entire database” link. Do a key word search and click on the attached document. This will bring up a complete listing of the records and photographs associated with your search.

Our new archives database is the first and only public archival database solely devoted to chiropractic. We are, I think justifiably, proud of it. •

REFERENCES

- Pope LS. Another incredible journey. Sentinel, October 1968; reprinted in the Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association 1970 (July);14(2):33.

- Keating, Joseph Jr. Flying Chiros, Part II of II. http://drnikel.com/FlyingChirosPartIIofII.aspx

- Simser, Guy. A daring young man in his flying machine. The Beaver, 2000 (June/July), 80(30): 15.

- Ibid, 11.

Steve Zoltai is the collections development librarian and archivist for CMCC and was previously the Assistant Executive Director of the Health Sciences Information Consortium of Toronto. He has worked for several public and private libraries and with the University of Toronto Archives. Steve comes by his interest in things historical honestly – he worked as a field archeologist for the Province of Manitoba. He can be contacted at szoltai@cmcc.ca.

Print this page