In Part 1 of The Body in Question, we took an historical perspective

and saw how the changing of attitudes towards human dissection over the

centuries shaped our understanding of the human body and how a shortage

of cadavers could lead to grave robbing and even murder.

In Part 1 of The Body in Question, we took an historical perspective and saw how the changing of attitudes towards human dissection over the centuries shaped our understanding of the human body and how a shortage of cadavers could lead to grave robbing and even murder.

|

|

| Legion Branch 450, 1951. Advertisement

|

Part 2 continues the story of human dissection in anatomy education with the Chiropractic Branch of war veterans’ pivotal role in CMCC’s acquiring the means to perform human dissections, a look at its most storied anatomist and the future of human dissection in anatomy education.

DISSECTING CMCC

Although anatomy was an integral part of the curriculum when the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (CMCC) opened its doors on September 18, 1945 – dissection itself was listed in the 1947 senior year curriculum1 – CMCC did not possess the legal standing to perform human dissection. The Board of Regents of the Drugless Practitioners Act, under whose jurisdiction CMCC fell, however was of the firm opinion that human dissection was an essential component of anatomy education and must be part of the new college’s curriculum.

This disconnect between what CMCC was directed to teach and what could actually be delivered necessarily brought the college and the Board into conflict. Accordingly, the Board instructed CMCC that the graduating class of June 1950 must have human dissection in order for graduates to continue to stand for licensing in Ontario.

In a letter from the Board to the Acting Minister of Health, The Honourable W.A. Goodfellow:

“On February 19th, 1949 the Board of Regents granted special and unusual permission to graduates of classes of June 1949 and January 1950 at the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College to sit for examinations in Chiropractic and to obtain registration as Chiropractors in the Province of Ontario, if they were successful in passing the examinations and could qualify in all other respects under the Regulations, Drugless Practitioners Act, Ontario” without human dissection.

“At the same time … CMCC … was notified .… that no further graduates of that school would be examined by the Board until it was able to conform to the full requirements of the Board, namely, by inclusion of human dissection in its curriculum.” 2

Although the college was initially allowed to produce graduates who would be eligible for licensing in Ontario without human dissection, the Board made it plain that future graduates must receive instruction in dissection. The clear implication of the directive was that CMCC graduates would be in the unusual and unacceptable position of not being eligible for licensing in the province in which they graduated and would be forced to leave Ontario to practice.

BRANCH 450 TO THE RESCUE

Obtaining the legal means to perform human dissection then, as now, was no mean feat. Listing in the provincial Anatomy Act was necessary for CMCC to be permitted human dissection and obtaining the required status was a serious challenge. Timing, however, is everything and CMCC was fortunate in that members of its early student body were well positioned to lend support to the effort. The majority of CMCC’s early classes were composed of Second World War veterans, many of whom had leadership roles in the military. In the estimation of CMCC historian, Dr. Douglas Brown, the veterans were a singularly dynamic and influential group. When faced with the Board’s June 1950 deadline, the cause was taken up by the Chiropractic Branch of the Canadian Legion, which used its political contacts in government to spearhead the effort to bring human dissection into the curriculum.

|

|

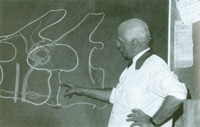

| Dr. Duckworth illustrating anatomical structures.

|

Twisting arms and calling in favours paid off. In CMCC past president Dr. Ian Coulter’s recollection, one provincial member of parliament exclaimed that if Second World War veterans who were studying to become chiropractors at CMCC “were good enough to fight for their country, and risk their lives, they were certainly good enough to practice anatomy.” On December 9, 1949, CMCC was notified by the Minister of Health that the college was permitted dissection privileges3 and on April 6, 1950, an Order-in-Council was passed listing CMCC among teaching institutions eligible to receive cadavers for dissection purposes. Though the order was passed too late for the graduating class of 1950 to obtain bodies for dissection, the Board reversed its earlier decision in light of the genuine efforts of all involved, thereby enabling the class to sit for examinations and obtain licensing in the province.4 CMCC’s listing in the Anatomy Act of Ontario permitted the college to teach human dissection along with, at that time, only six other universities and colleges. CMCC was the only non-medical teaching institution among them named as a recognized school of anatomy and the class of January 1951 became the first to receive instruction in human dissection.5

NO SMALL FEAT

The accomplishment is no less significant today as CMCC is one of only nine other academic institutions that offer human dissection as part of anatomy education. These include the six medical schools, the University of Guelph and the University of Waterloo (which maintain kinesiology programs) and Humber College, which has a program training morticians. Indeed, access to human dissection was one of CMCC’s attractions in its negotiations for affiliation with York University in recent years.

According to Dr. Howard Vernon, CMCC’s director of the Centre for the Cervical Spine, given the antagonism between chiropractic and orthodox medicine in the early days it would not be surprising if challenges to CMCC’s listing in the Anatomy Act would have occurred. “The 1950s and ’60s”, he notes, “was a time of great tension between the profession and the mainstream medical community. The medical community was very strong and often used physiotherapy as a proxy to stir up controversy. The college likely went through the period facing challenges and to have sustained the anatomy lab as a pearl would have been a major accomplishment.”

THE LANDSCAPE TODAY

CMCC and the other designated institutions are registered as schools of anatomy with the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario. Current regulations in the Anatomy Act of Ontario stipulate that bodies must be willed for medical education and research purposes. Cadavers are distributed through the Coroner’s Office to qualifying institutions. In the past, the Act allowed unclaimed bodies to be used for medical research; however, in the late 1990s advocates for the socially disadvantaged raised opposition based on the objection that practices at the time did not provide dignified burial for society’s marginalized.

Ironically, CMCC has always provided a formal service recognizing the importance of the human donation and regulatory changes have the potential to create a modern round of shortages of bodies for research and anatomy education.

DUCKIE TALES

Perhaps the most storied member of the anatomy department was Dr. John Duckworth – Duckie, to his colleagues. Ambidextrous, Duckworth could draw the most intricate anatomical illustrations on the blackboard using both hands simultaneously. Famously known to lick his ungloved fingers during dissections, Duckworth is also reputed to have confessed to colleagues, perhaps in jest, that he had participated in the Resurrection trade during his medical student days in Edinburgh and once notoriously quipped: “Grant and I” – referring to the author of a classic anatomy text still in use today – “performed thousands of dissections. Then Grant died. And I dissected him.”

For all his quirks and mannerisms, Dr. John Duckworth had a profound impact on the quality and standard of anatomy education at CMCC. Duckworth joined CMCC in 1979 after retiring from the anatomy department at the University of Toronto at age 65. A Queen’s Physician, frequent government consultant and highly respected anatomist, Duckworth was instrumental in redefining how anatomy was taught at CMCC and his teachings have influenced generations of chiropractors.

Duckworth spent 50 years teaching at the University of Toronto and was chair of the anatomy department under the previously mentioned Dr. Grant (author of Grant’s Atlas). He was originally hired on short-term contract to mentor Dr. Bill Peek, the only other member of the anatomy department, to enable Peek to teach gross anatomy. Duckworth ended up taking over Peek’s gross anatomy lecturing responsibilities and stayed until his own death 16 years later. According to Dr. Ian Fraser, past chair of CMCC’s biological sciences department, Duckworth was a classically trained, old school anatomist of encyclopedic knowledge who strongly believed in the primacy of dissection in teaching. “His hiring,” states Fraser, “brought a tremendous amount of knowledge, passion and expertise to the anatomy department and was fundamental in raising the level of anatomy education at CMCC.”

Duckworth quickly established himself as the first key figure in the anatomy department and was instrumental in setting up relationships with the Chief Coroner’s Office to develop a viable body donation program. Before Duckworth, acquisition of bodies was uncertain and sporadic and cats were frequently used in place of human cadavers. The program he set in place marked the transformation of the anatomy department into a modern, fully enabled teaching entity with the tools essential to delivering first-rate anatomical instruction.

Duckworth, however, was uninterested in administration and tired of lecturing. So when the department chair became available in 1989, he did not apply but elected, instead, to reinvent himself as a lab demonstrator in order to dedicate himself to his first love: dissection. He was so convinced of the importance of human dissection in anatomy education that he believed there really was no acceptable alternative. According to Dr. Peter Cauwenbergs, longtime colleague and former chair of the anatomy department, “Duckworth and I shared the belief – and I continue to believe – that the best way to teach and the best way to learn anatomy is by doing dissection.”

John Duckworth died in 1995, in his 80s, still teaching at CMCC. So influential was his teaching that CMCC created an anatomy museum to commemorate his many contributions. In 1997, CMCC dedicated the Dr. John Duckworth Museum of Anatomy in his honour. The collection includes many of Duckworth’s own dissections. Brilliant, quirky, much loved and respected, Duckworth’s memory continues to inspire excellence in anatomical instruction. In Dr. Fraser’s opinion, at least, “we are unlikely to see his kind again.”

THE FUTURE OF DISSECTION

Western medicine attempts to isolate the mechanisms of disease and cure it. Without a realistic understanding of the arrangement of the human body, the process becomes problematic. Nonetheless, the use of human dissection in teaching remains controversial.

|

|

| Three-dimensional imagery based on medical scans may enhance anatomy teaching and learning. Whether virtual reproductions of the human body will ever replace dissection is, however, an open question. Image courtesy and copyright Primal Pictures www.anatomy.tv. |

Some have argued that dissections have a negative impact on students’ respect for patients and human life. Others have stated that while hands-on experience is essential, alternatives such as plastinated or freeze-dried cadavers are just as effective in the teaching of anatomy while reducing the number of cadavers required. Instructional videos, plastic models, and printed materials also exist. Some studies find them equally effective as dissection while other research questions the usefulness of substitutes.6, 7

Given recent advances in digital imaging, can virtual dissections take the place of actual hands-on? Dr. Howard Vernon believes that, for institutions that do not have human dissection, advances in electronic modeling may already be deemed sufficient so they do not have to pursue dissection. He notes a strong traditionalist approach in the dissection controversy but believes, from a learning point of view, structures may eventually be adequately demonstrated using advanced video imaging. Technologies of this kind could include three-dimensional scanning, enabling projected holograms which could be linked with electronic gloves and a virtual reality interface. Dr. Vernon, for one, would not be surprised if all of this comes together in a classroom setting to allow virtual dissection at some time in the future.

Future technologies have the potential to ultimately eliminate the need for anatomy labs and cadavers altogether. If this is not likely to happen any time soon, it is foreseeable on the horizon and at some point the use of human dissection may look as strange and passé as the mortsafes that were intended to foil Resurrectionists in the not too distant past.

Duckworth would be appalled.

Afterword: If you have been entertaining thoughts of the afterlife lately, perhaps it is time to consider CMCC’s Body Donation Program. Contact Sarah Hockley at shockley@cmcc.ca for specifics.

References:

- Keating, Joseph. “Chronology of the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (CMCC)”, unpublished manuscript, p. 21.

- Ibid: p. 33.

- Keating, Joseph. “Chronology of the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (CMCC)”, unpublished manuscript, p. 31.

- Ibid: p. 33.

- Cornerstone, 1951, p. 44.

- Azer, S.A. and N. Eizenberg. “Do We Need Dissection in an Integrated Problem-Based Learning Medical Course? Perceptions of First- and Second-Year Students.” Surgical Radiologic Anatomy. 29:2 (March 2007); pages 173-180.

-

Parker, Lisa M. “What’s Wrong With the Dead Body? Use of the Human Cadaver in Medical Education.”

Medical Journal of Australia. 176:2 (2002); pages 74-76.

Steve Zoltai is the collections development librarian and archivist

for CMCC and is a member of the Canadian Chiropractic Historical

Association. He was previously the Assistant Executive Director of the

Health Sciences Information Consortium of Toronto. He has worked for

several public and private libraries and with the University of Toronto

Archives. Steve comes by his interest in things historical honestly –

he worked as a field archeologist for the Province of Manitoba. He can

be contacted at szoltai@cmcc.ca.

Print this page