A multidisciplinary overview of spinal cord injury

By Maria DiDanieli Sean Pothier* Angela Sarro RN(EC) MN CNN(C)** Tammy Scott BSc Kin***

Features Clinical Techniques spinal cord spinal injury spine health World Federation of Chiropractic world spine day“I was about to graduate university in France; I was athletic, having taught skiing at Mont Tremblant, sailing and windsurfing in four Club Meds; I was a fashion model in Old Montreal. I couldn’t believe that this injury was permanent – I had so much going for me.”

|

|

| MRI showing injury to the spinal cord.

|

When Sean Pothier, a resident of Montreal and avid spokesperson with ThinkFirst Canada – a nationwide charity dedicated to the prevention of spinal cord and brain injuries – looks back, coming to terms with the permanence of his injury was the biggest wall he remembers climbing. It was through ThinkFirst that Sean encountered Rick Hansen, who is well known for a spinal cord injury (SCI) that landed him in a wheelchair at the age of 15, but well loved and respected for his accomplishments after that. Pothier tells Canadian Chiropractor that, while he was still struggling with the fact that his own injury was for life, he derived a new direction from Hansen, who said to him, “Sean, like mine, your life has changed forever. So, never look at things that you used to be able to do. Now, you have to enjoy things that you can do in your new body. But, don’t enjoy them with your old body expectations – enjoy them with your new body and what it is able to do. You can still live the same quality as before – just don’t have the same expectations.”

The month of May is recognized across Canada as Spinal Cord Injury and Canadian Paraplegic Association (CPA) awareness month. Aligned with this mission to raise knowledge and awareness, and in honour of injury survivors, this article will provide a multidisciplinary overview of SCI. It is not the intent of the article to be a comprehensive review of this vast and complex topic, but, rather, to provide some initial information in the hope of springboarding further, and much-needed, involvement by members of the chiropractic profession in this area.

INTRODUCTION AND EARLY STAGES FOLLOWING SCI

Injury to the spinal cord can occur as a result of trauma or can be precipitated by certain non-traumatic activators, including infectious or inflammatory disorders and motor neuron diseases. Traumatic injury most commonly results from motor vehicle accidents and/or sport or recreation related injury, but can also be caused by work accidents, falls, violence or birth injury. In December 2010, Canada reported a total of 1,785 new traumatic SCIs and 2,474 new non-traumatic SCIs.

In traumatic situations, the initial factor precipitating SCI is mechanical and involves compression and/or traction of the cord. Compression may occur due to displaced bone or bone fragments, ligaments and/or disc debris. Injury to blood vessels and cell membranes, as well as cord swelling, in the area of impact initiate a cascade of events that result in disruption of autoregulation of blood flow and axonal propagation leading, eventually, to spinal shock. Toxins that are released through broken cell membranes in the spinal grey matter, as well as electrolyte shifts in the area of injury, spark a process of secondary injury that eventually spreads to white matter, killing viable neural cells and further disrupting axon flow at, and below, the level of impact. The processes involved in non-traumatic spinal cord injury may bear some similarity to this cascade of events, but are, in their details, largely specific to the disease that is responsible for the injury.

Acute assessment of an SCI includes use of functional grading scales and imaging – mostly MRI – to determine the level and extent of injury, whether the injury is complete (i.e., no sensation and/or function below the level of injury) or partial (i.e., some preservation of neural function below the level of injury), and presence of comorbidities (including brain injuries, as these are a common combination). Electrophysiology may be employed to help characterize the injury if the patient is not responsive.

Treatment, at this phase, is largely aimed at neuroprotection and sheer preservation of life. Neuroprotective strategies mostly involve focusing on the effects of secondary injury. Pharmacological agents are employed to assist with inflammation, electrolyte imbalance and removal of toxic agents – being expelled in large quantities from disrupted cells in the area of injury. Surgery may be indicated, either to remove fragments threatening the spinal canal and/or to stabilize the spine. External stabilization/traction devices have also been employed.

The post-injury course experienced by an SCI patient varies, in its many elements, from patient to patient, and requires the combined efforts of a team of practitioners and therapists in medical and rehabilitative disciplines.

|

Acute and long-term course and care

By Angela Sarro

The early stages

Some SCI individuals will require management in the intensive care unit with ventilatory support until their respiratory function improves. If ventilation is prolonged, then a tracheostomy may be required. Invasive monitoring, which includes intravenous therapy, arterial lines, central venous catheters and cardiac monitoring, is not uncommon. Some individuals may be placed in halo traction to try to realign the spinal column prior to any surgical intervention. Astute nursing care during the acute phase is of utmost importance to provide the necessary day-to-day care, along with emotional support, to help the individual cope with his/her injury.

Some individuals may require the placement of a nasogastric or gastrostomy tube for enteral feeding. These measures are usually temporary. The assistance of a speech language pathologist will be crucial to monitor swallowing mechanisms for safety of oral feeding. Once oral intake of nutrients is deemed safe, the diet is advanced from liquids to solid foods as tolerated.

Because sensory impairment and motor function are often affected, the SCI individual is prone to skin breakdown. The use of a special pressure-reducing mattress, and a regular turning schedule, often every two hours to relieve pressure areas, is an important aid in preventing skin breakdown.

Bowel and bladder management are important aspects both in the early stages and long term. Initially, while in hospital, individuals will have a Foley catheter in place. Once the individual is medically stable, the catheter is removed and the bladder is monitored for any spontaneous activity. If unable to void, an intermittent catheterization protocol is set up. An effective bladder management program is important to prevent urinary infections and allow the bladder to be emptied at a convenient time.

Prevention of infection is very important in SCI. Three common infections include urinary tract infection, pneumonia and skin breakdown. These three in combination could result in death due to the impact on the individual’s overall ability to combat them.

Physiotherapy and occupational therapy in the acute care phase focus on early mobilization of the individual. This will become more of a focus in rehabilitation, at which point methods for learning to become as independent as possible will be important.

Considerations in the short and long term

A spinal cord injury is a devastating event for any individual. It impacts both physical and psychological aspects of one’s day-to-day activities. An individual who was completely independent in all facets of life is now dependent on someone else to do even the

simplest things.

This dependency varies based on the extent of injury. An individual with an incomplete SCI may be able to regain some of the initial loss of function to varying degrees, whereas, a complete spinal cord injury will require the individual to have daily support and care for most activities for the remainder of their lives. Most patients require day-to-day care for bathing, turning, eating and toileting. The simplest things, such as eating, or getting in and out of bed, may require the assistance of one or more people.

Psychosocial issues faced by the SCI individual, both in the short and long term, include anxiety, body image disturbance, grieving, ineffective coping, feelings of powerlessness and depression. Quite often during the acute period, individuals display feelings of anger, resentment and denial. Depending on previous coping mechanisms or situations they may have been faced with, this period varies.

Essential at this time is ongoing support and reassurance by the family and health-care staff, spiritual care and outside support groups to help with coping mechanisms.

Living with an SCI can be very stressful. Stress-related symptoms can delay recovery and make other problems, such as pain and spasticity, worse. Addressing this stress with a specialist, such as a rehab psychologist, can help with the development of skills and strategies for managing stress.

In the short term, survival from the injury itself is the main focus. If the trauma resulted in other injuries, the transition from acute care to rehabilitation may be prolonged. Often the biggest hurdle for the individual, following an SCI, is the acceptance of the injury and the impact it will have on their lives moving forward.

Long-term care needs of an individual with an SCI are also determined by the level and the type of injury. A tetraplegic with little or no arm function will require attendant care to a much greater degree than a paraplegic who has learned how to self-transfer, dress and perform intermittent catheterizations. Attendant care programs are available to provide assistance with routine activities of daily living due to these physical limitations. The amount of care available will determine the degree of independence patients can have.

Elements that need to be taken into consideration, when looking at long-term needs of an individual with SCI, include housing, home modifications, transportation, education and employment, income maintenance, mobility aids, and supports required to maintain an active and productive life.

The injured person’s family

It is often easy to forget about the families of SCI patients during the acute phase of admission to hospital. It is important to remember that they, too, are going through a period of trauma, more psychological than physical. Emotional support for family members is crucial so that they can remain strong to support their loved ones as they recover. Support groups for families of spinal cord injured individuals can help them deal with their feelings and fears about the present and the future.

|

REHABILITATION AND FUNCTIONAL RECOVERY

Research findings and clinical goals

by Tammy Scott

With clinical and basic science research leading to new advances and prolonged survival becoming an attainable goal in spinal cord injured patients, rehabilitation of these injuries has an increasingly important role. The primary goals of rehabilitation are prevention of secondary complications, maximization of physical functioning and reintegration into the community.

Rehabilitation following SCI is most effectively undertaken with a multidisciplinary, team-based approach. Physical therapists typically focus on lower-extremity function and on difficulties with mobility as well as address upper-extremity dysfunction and difficulties in activities of daily living. Although each team member has primary responsibilities, any member of a properly functioning interdisciplinary team can contribute to the resolution of any problem.

Even by itself, aggressive physical rehabilitation is a complicated area in which improvements may be due to many causes and mediating physiological mechanisms.

First, such rehabilitation most likely stimulates some function-restoring neuronal regeneration, adaptation, and/or reconfiguration (i.e., plasticity). It also may activate dormant but intact neurons that transverse most injury sites, even injuries clinically classified as complete. Studies suggest that only a small percentage of “turned-on” neurons are needed to regain significant function.

Second, the spinal cord by itself possesses intelligence and is not completely subservient to brain oversight. Specifically, the spinal cord’s “central-pattern generator” can sustain lower-limb repetitive movement, such as walking, independent of direct brain control. Extensive training coupled with braces thoroughly stimulates this neural network and can result in ambulation.

Third, many muscles above the injury site indirectly affect ambulation, especially through the use of leg braces. For example, the latissimus dorsi muscles, which are innervated from the cord’s cervical region, influence pelvic-area movement and, in turn, ambulation.

Fourth, aggressive physical rehabilitation is often initiated in the first year after injury, a period in which appreciable recovery potential exists. Critics have suggested that any functional recovery, no matter how dramatic, would have happened anyway in this time period.

Project Walk

Many people with SCI who have committed to Project Walk – an intensive exercise-based recovery program developed by

Ted and Tammy Dardzinksi in Carlsbad, California, that attempts to re-educate the damaged nervous system through physical stimulation (www.projectwalk.org) – have gained function much beyond what was considered possible after injury. Project Walk focuses on developing muscle potential below the injury level. The Dardzinksis believe standard rehabilitation programs not only ignore this potential, but contribute to its extinction by “tossing-in-the-towel” focusing on non-paralyzed body parts needed for adaptation to wheelchair living instead of ambulation. They also believe that extensively administered anti-spasticity medications are the equivalent of pouring water on the flickering embers of regeneration that often still exist after injury. In contrast, Project Walk’s goal is to fan these embers to promote functionality below the injury level. Believing there is a post-injury therapeutic window in which the recovery potential is greatest, advocates of Project Walk ideally would like to start treating patients relatively soon after injury. Each program is individually tailored to one client.

Proponents of the program believe that without proper stimulation and load bearing, a newly injured person will soon start losing bone density, muscle mass, and CNS functioning, which makes future recovery even more difficult. Although the program has treated many after this window, sometimes with dramatic improvements, much more effort is needed.

The average client works out three hours every other day. For people returning home, individually tailored, home-based programs are designed. Although intensive, clients are encouraged not to embrace these programs exclusively at the expense of overall life balance achieved through involvement in areas such as career, school, social life, etc.

Functional improvements include increased muscle mass, CNS activity, health and well-being, sensation and function below the injury level, occupational skills, and sweating, as well as decreased drug dependence and decreased pain. Project Walk emphasizes good nutrition, and encourages the use of synergistic healing modalities, including acupuncture, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, standing frames, FES bikes, and other electrical stimulation that helps to maintain muscle mass and circulation.

|

The role of chiropractic

by Dr. Richard Hunter

Chiropractors are underutilized in the field of spinal cord injury. The altered movement patterns seen in SCI commonly contribute to biomechanical problems of the kind chiropractors regularly see in their practices. Restoration of normal joint and soft-tissue function is paramount to help reinstate ability, and to reduce joint and nerve pain syndromes. This is accomplished with the use of corrective chiropractic techniques.

Joint and muscle proprioceptors are also affected by partial and complete spinal cord lesions. Afferent messages to the cord and brain are affected. Some proprioceptive input is reduced or absent, whereas other input is excessive or aberrant due to the altered biomechanics of the joint, muscle and overall locomotor system.

When deprived of the usual stimulus it normally receives, the cortical map of the body in the brain can cause the central nervous system to promote secondary pattern changes. These mixed messages may have an influence on the brain and the spinal cord’s neuroplasticity, causing adaptations that may have negative behavioural consequences. It is essential, then, that proper joint and body motion be restored as quickly as possible following a spinal cord lesion in order to keep the nervous system stimulated and promote proper reorganization and mapping of the neural pathways. Active and passive forms of therapy, including chiropractic, are very helpful at this stage of healing. As long as the lesion and spinal injury is stable, many forms of restorative techniques and exercise can be used.

Chiropractors have excellent skills in observation and palpation that enable them to detect alignment issues as well as subtle joint, nerve and muscle problems that cord injured patients have. These problems can be detected and helped with the skills chiropractors have. I believe that early intervention using chiropractors will improve the early treatment results and the long-term management of spinal cord injured patients.

PREVENTION, THE ONLY CURE

Formidable advances have been made to mitigate some of the catastrophic sequelae of spinal cord injuries, and more is being learned from year to year. However, at this time, an actual method for reversing the effects of an SCI has yet to be determined. For this reason, prevention still really is the best and only cure.

Prevention of injury may, of course, be discussed between practitioners and patients in the clinic setting. Chiropractors may also choose to talk about this in the health classes that many of them hold for their patients and/or within their communities. Furthermore, many DCs are involved with organized sports, both at the amateur and professional levels. This is an area where many injuries may occur, and thus, an opportunity for DCs to incorporate prevention education into their role with the team.

Chiropractors may also become involved in existing organizations that are dedicated to public education regarding spinal cord injury prevention. (Initiatives for the prevention of spinal cord injury are often paired with brain injury prevention education.) As spinal specialists, chiropractors are well versed in spine health – as holistic practitioners, they understand the importance of maintaining one’s lifestyle by not shying away from activities but learning to undertake them safely.

|

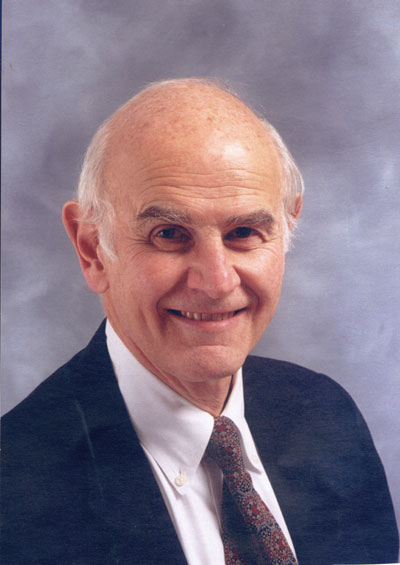

Interview with Dr. Charles Tator

ThinkFirst Canada (www.thinkfirst.ca) is one example of an organization that is dedicated to spine and brain injury prevention, but its approach has been somewhat different from that of similar groups. The organization was founded in the United States and brought into Canada by Dr. Charles Tator. Dr. Tator is a neurosurgeon, scientist and educator in the area of spinal cord injuries and their prevention. He has been the face of “ThinkFirst Smart Hockey”, as well as injury prevention initiatives in other amateur and professional sports on the local regional and national levels for a number of years. Dr. Tator found himself aligned with ThinkFirst’s (US) notion that prevention efforts should begin as early as possible in a person’s life. From that premise, ThinkFirst Canada was born.

ThinkFirst centres its efforts on educating children of all ages about the advantages of playing safe while having fun.

|

|

“ThinkFirst is involved in programs to reduce the incidence of spinal cord and brain injuries through school and community-based injury prevention initiatives,” Dr. Tator tells Canadian Chiropractor, from his office at the Krembil Neuroscience Centre of the University Health Network in Toronto. “The latter include many sport-specific programs and are focused on a variety of sports and recreational activities, including hockey, football and diving. Shallow water diving is still the most common cause of spinal cord injury among the sports and recreational activities in Canada. We try to teach activity-specific strategies and try to work in a coalition with other organizations such as the Red Cross.”

ThinkFirst, a not-for-profit organization, designs and develops its programs and operations based on research that explores the impact of prevention programs in decreasing the incidence of injuries in various situations.

“One of the exciting findings [of this research] is that prevention programs do make a difference,” continues Dr. Tator. “For example, there are fewer broken necks in hockey as a result of a number of injury prevention strategies, including education of players, coaches and trainers, as well as through rules changes and enforcement. Seatbelts and airbags have reduced the number of spinal cord injuries in motor vehicle crashes.”

There is still work to be done, however, to bring ThinkFirst, and initiatives like it, closer to fulfilling the vision of completely abolishing traumatic spinal cord (and brain) injury. Even to meet its goal of measurable reductions in these types of injuries, ThinkFirst must continue to partner with volunteers and organizations who are equipped to get the right messages out. This is an opportunity for a chiropractor who is interested in supporting prevention initiatives by volunteering, and/or by starting a ThinkFirst chapter in his/her community.

“We need to reach a larger number of participants with specific educational programs about avoidance of risk-taking behaviour,” notes Dr. Tator. “For example, the damaging mixture of alcohol and water activities, or alcohol and snow activities, requires greater

emphasis.”

For chiropractors who work with athletes at any level he adds, “Detecting spinal instability in athletes is another important area of prevention.”

Gleaning an understanding of those who live with SCI and the nature of their injuries is the first step to contributing one’s expertise as a practitioner to this costly area of health care, and its many devastating effects. Much work has been done, but much more is needed in the areas of care and rehabilitation, prevention and research. According to the Canadian Paraplegic Association – a group whose mission it is to assist those living with spinal cord injury by providing information, assistive equipment, employment and more – there’s plenty that can be done and it begins with knowledge and awareness.

My sincere thanks go to all who participated in this article, including Sean Pothier (who is actually a brain injury survivor but shares many of the challenges and needs as well as the hope and courage of SCI survivors) for his candid participation. I would also like to thank Rebecca Nesdale-Tucker, executive director for ThinkFirst Canada, for her assistance.

*Sean Pothier is a Voices for Injury Prevention (VIP) volunteer spokesperson for ThinkFirst Canada. (VIPs with ThinkFirst are injury survivors who teach injury prevention.) He also developed the Handicap Ski program at Mont Tremblant in Quebec.

**Angela Sarro RN(EC), MN, CNN(C), is a nurse practitioner in the Spine Program at the Krembil Neuroscience Centre, Toronto Western Hospital. (angela.sarro@uhn.on.ca)

***Tammy Scott, BSc, Kin, is a kinesiologist at Great Lakes Physiotherapy in Simcoe, Ontario. She has worked in acute and chronic care settings with motor vehicle accident patients, workplace injuries, sports injuries and return-to-work plans. (tammy@greatlakesphysiotherapy.com)

†Richard Hunter, DC, is a co-founder of the Vancouver Spine Care Centre in British Columbia and has worked with a number of spinal cord injury patients, including Rick Hansen. (drrichardhunter@shaw.ca)

††Charles H. Tator, CM, MD, PhD, FRCS(C), FACS, is currently a professor of neurosurgery, University of Toronto, Division of Neurosurgery, and founder of ThinkFirst Canada. (Charles.Tator@uhn.on.ca)

Print this page