Shoulder complaints are frequently heard in a chiropractic office. In

many cases, these shoulder injuries are the result of a sports-related

incident. Athletes put their bodies through tremendous physical strain,

and since the shoulder has insufficient stability, injury is the result.

A special thank-you goes to my good friend Dr. Rob Jones of Lawrence, Kansas, for his tremendous contributions to the ART section of this article.

Shoulder complaints are frequently heard in a chiropractic office. In many cases, these shoulder injuries are the result of a sports-related incident. Athletes put their bodies through tremendous physical strain, and since the shoulder has insufficient stability, injury is the result.

Research indicates that chiropractic care can have a positive effect on shoulder injuries.1,2 However, most of the literature focuses on treatment for supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles. There is very little research available regarding treatment for other rotator cuff muscles, such as the teres minor, and even less discusses chiropractic adjustments for the shoulder.3

In this edition of Technique Toolbox, I will discuss a specific shoulder injury that affects the glenohumeral joint, and the teres minor. I will then discuss Minardi Integrated Systems, and Active Release Technique, which will be combined to correct both the subluxation pattern and the muscular component involved.

|

|

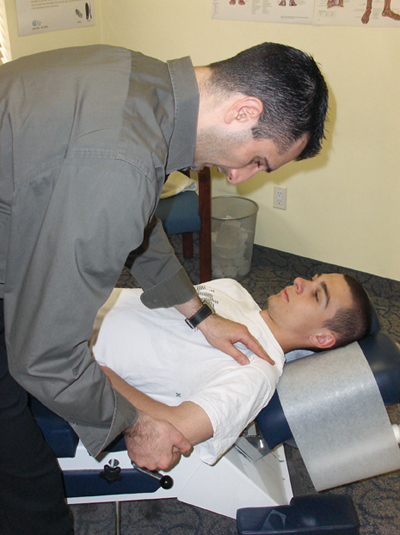

| Picture 1: Teres minor muscle test. Doctor applies P-A pressure to elbow while patient resists, in chicken wing position. |

Case Study:

A 21-year-old male football player presents with posterior shoulder pain. The patient notifies the doctor that he was tackled from behind in a game last night. The patient states that, in an attempt to not fumble the ball, he landed on the point of his bent elbow as he was taken to the ground. The fall resulted in immediate pain in the posterior aspect of the shoulder. Physical examination reveals pain and swelling upon palpation on the affected side. Examination also reveals a loss of strength with adduction and external rotation. Circumduction is also limited. Neurological and X-ray analyses are unremarkable.

This type of fall, and corresponding physical exam findings, is the typical clinical scenario that would be present in a patient who has sustained a posterior humerus subluxation. This indicates that the humeral head has subluxated into posterior translation, through the glenohumeral joint, with subsequent damage to the teres minor muscle.

For the subluxation component, I have developed the Minardi Integrated System (MIS), also known as the Complete Thompson Technique. This is an expansion on the Thompson Technique, an incorporation of my own work with that of Stucky and Thompson, to form a comprehensive full-body adjusting procedure. Extremity analysis and adjusting are just some of the new additions have been incorporated into the Thompson Technique to fill in any gaps that existed previously.

Following the case study presented earlier, the first step using MIS is to confirm that the patient indeed has a posterior humerus subluxation.

Step 1: Doctor must perform a teres minor muscle test: (See Picture 1)

- Patient: supine, affected arm in the “chicken wing” position (affected arm and elbow bent at 90 degrees, hand tucked under the patient’s pelvis).

- Doctor: on affected side.

- Procedure: doctor takes hold of patient’s elbow, applies P-A pressure, and instructs the patient to resist, while maintaining their arm in this position. (This resistance, while in the chicken wing position, applies external rotation and adduction to the affected arm. The only muscle that performs both of those functions is teres minor).

- Normal: If a posterior humerus subluxation is not present, the patient will be able to resist the doctor’s pressure, and keep the arm in the same position.

- Subluxation: If the patient is unable to resist the doctor’s P-A pressure, and is unable to maintain the arm position; this confirms that the humerus has subluxated posteriorly, and that the teres minor is damaged. Once this is confirmed, move on to Step 2.

|

|

| Picture 2: Doctor position for a posterior humerus subluxation adjustment. |

Step 2: Correction: Posterior Humerus Prone Adjustment. (See Picture 2)

- Patient: Prone, involved arm straight and extended 45 degrees.

- Doctor: On affected side, facing cephalad.

- Table: Dorsal piece in the ready position, or toggle board under the affected area.

- Contact 1: Web contact of medial hand on posterior surgical neck of the humerus.

- Contact 2: Lateral hand grasping wrist of involved arm.

- LOC: Contact 1: P-A. Contact 2: Long axis distraction.

For treatment of the muscular component of this injury, I would recommend using Active Release Techniques (ART). ART was born out of Dr. Michael Leahy’s observations of the myo-fibrotic changes associated with macro and micro traumatic injuries. Dr. Leahy noted that injured tissue tended to become shortened, denser and coarser than adjacent non-injured tissue upon palpation. Due to injury, adhesions form within the muscle. The goal of ART is to remove these adhesions by actively lengthening the muscle, while simultaneously working through the grain of the muscle fibre. Once the adhesions are removed, the muscle is restored to a balanced state.

The teres minor arises distally from the superior lateral border of the scapula and traces superior laterally toward the humeral head, where it attaches inferior to the greater tubercle.

|

|

| Picture 3: ART for teres minor, starting point.

|

|

|

|

| Picture 4: ART for teres minor, finish point.

|

Step 3: ART for teres minor (Applied to adhesion site or entire muscle. See Pictures 3-4.)

- Doctor: On affected side.

- Patient: Prone or seated while actively moving affected arm.

- Contact: Thumb pad at adhesion site.

- Stablilization Hand: On thumb contact.

- Active Patient Movement: Patient motion starts with the humerus fully adducted with the elbow bent to 90 degrees. Doctor takes his/her contact. Patient slowly reaches the humerus forward (into flexion), extends the elbow and internally rotates the humerus by turning the thumb toward the floor. The finish position is reached when the humerus is in full flexion, the elbow is fully extended and the humerus is internally rotated with a thumb down position.

- LOC: If the doctor is attempting to treat the scapular portion of the muscle, tension is drawn along the muscle from distal to proximal, moving toward the humerus along the fibers of the teres minor. When attempting to treat the humeral end of the muscle, line of drive is toward the scapula. Always apply non-compressive tension.

By using a combination of adjustments with muscle procedures, as in this case, shoulder injuries can be treated more effectively. As usual, I have only scratched the surface with these individual techniques. If you would like to learn more, please visit www.active-release.com, and www.ThompsonChiropracticTechnique.com .

If you would like to see a specific technique featured in a future edition of Technique Toolbox, please email me at johnminardi@hotmail.com .

Until next time…Adjust with confidence!

References

- Daniel, DM. Diagnostic Corner. An overview of the scientific literature relating to the diagnosis and treatment of shoulder impingement syndrome. DC Tracts. 2008. 20(2): 9-12.

- Will, LA. A conservative approach to shoulder impingement syndrome and rotator cuff disease: a case report. Clin Chiropractor. 2005 Dec;8(4):173-178.

- Atkinson, M. A randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of shoulder manipulation vs. placebo in the treatment of shoulder pain due to rotator cuff tendinopathy [clinical trial; randomized controlled trial]. JACA Online. 2008 Dec; 45(9):Online access only p 11-26.

Print this page