The ABCs of Rehabilitation

By Rocco Guerriero BSc DC FCCSS(C) FCCRS FCCO(C)

Features Clinical TechniquesIntegrating rehabilitation into your chiropractic practice

FCEs, FAEs, ADLs, MMI, PDAs, NDI, MVA and ROM, some of the common acronyms associated with rehabilitation, should be part of the everyday vocabulary of heath-care practitioners.

FCEs, FAEs, ADLs, MMI, PDAs, NDI, MVA and ROM, some of the common acronyms associated with rehabilitation, should be part of the everyday vocabulary of heath-care practitioners.

Multidisciplinary rehabilitation became popular in the early 1990s when there was a realization that no single health-care provider could fully rehabilitate an individual. Mayer and Gatchel had coined the term “functional restoration program” in the late 1980s. With innovation, and policy and regulation changes, Canadian chiropractors began to set up rehabilitation clinics in the face of political challenges. Some insurers showed surprise that chiropractors were providing active therapy, and some physiotherapists were wary about chiropractors entering their turf.

Today, third-party payers expect chiropractors to provide some form of active therapy, referring to this as “activation.” At the very least, most chiropractors do prescribe home-based exercises for their patients.

This article will review basic components of rehabilitation that can be integrated into chiropractic practice.

Let’s start off with the definition of rehabilitation. Rehabilitation is a progressive, dynamic, goal-oriented, time-limited intervention, which enables an individual with an impairment to reach their optimal functional level (adapted from the World Health Organization).

Chiropractors must be able to assess function and adopt a functional rehabilitation model, using best practices and evidence-based care. Both chiropractor and patient need to recognize the paradigm shift from a pain model to a functional model.

Why is it important to assess function? Well, after all, restoration of function is the primary goal of rehabilitation, and function will provide a measurement for outcome-based care. We must determine our patient’s disability status, return-to-work capabilities, and any activity limitations, and then devise a goal-oriented patient program. However, in my experience, fewer than 50 per cent of patients require a formal rehabilitation program. For most, passive therapy including chiropractic adjustment and some home-based exercises are adequate goal achievement.

FUNCTIONAL TESTING

Low-tech testing is easy to integrate into practice. Let’s review the basic components of functional testing, incorporating outcome measures.

Functional Capacity Evaluations (FCEs) are a standardized battery of tests that determine an individual’s ability to return to work as well as the need for further rehabilitation. Performance on FCEs is influenced by physical factors in addition to the patient’s perceptions of disability and pain intensity. Psychosocial factors have been shown to influence measures of sincerity of effort during the FCEs. Effort level can be observed through visual observation.

How does measuring a patient’s lifting abilities relate to return-to-work capability? Studies have shown that the greater the weight lifted from floor to waist, the greater the likelihood of return to work.

The chiropractor must consider safety issues first. Patient questionnaires, such as the PAR-Q and PAR-X forms, are important in risk management. Blood pressure measurement is a very significant safety screen in determining readiness for exercise or functional testing. For example, resting systolic blood pressure of more than 200 mm/Hg or diastolic pressure greater than 115 mm/Hg are relative contraindications for further functional testing or exercise prescription. Most of the absolute contraindications are related to cardiac pathology. (Further information is available through the American College of Sports Medicine Guidelines.)

A form developed at CMCC is designed to be helpful in a rehabilitation program. Its functional testing components comprise physical and general parameters, cardiovascular fitness level, flexibility, strength, endurance, and balance and coordination. General parameters include height, weight, and Body Mass Index. In addition to recording blood pressure, the chiropractor must examine heart rate and rhythm for abnormal cardiovascular risks. Cardiovascular fitness levels can be evaluated using standardized protocols. Balance and coordination can be tested with neurologic examination protocols or by timing the patient’s balance on one leg.

Assessing flexibility in the spine or extremity joints can be done visually. However, more valid forms of measurement make use of a cervical range of motion (CROM) instrument, a plastic goniometer, a digital inclinometer or universal inclinometer. Protocols in measuring range of motion can be found in the American Medical Association (AMA) Guides, 4th and 5th editions, and in Hoppenfeld (notably, Physical Examination of the Spine and Extremities). A plastic goniometer is sufficient to measure range of motion in the extremity joints.

For strength testing, the chiropractor can use the Jamar hand and pinch grip dynamometers to help evaluate upper body strength, to assess a patient’s functional deficits, and to give an outcome measure. Having a patient hoist and carry weights in a milk crate is a simple way to assess lifting and carrying capacity. The Nicholas Manual Muscle Tester is one way to measure strength of the extremities; a Chattilon gauge gives indication of push-and-pull strength. Strength can be more comprehensively tested with costlier computerized testing units such as the ARCON, Hanoun and the ERGOS Work Simulator.

Patients with low back pain typically have an unbalanced relationship between abdominal musculature, the back extensor muscles and the lateral musculature of the core. Dr. Stu McGill, of the University of Waterloo, and others have shown that muscle endurance of the core can be reliably tested using the side bridge test, the abdominal endurance test and the back extensor (Sorenson’s) test. A simple neck endurance test to ascertain the endurance of the deep neck flexors does not require any high-tech equipment.

OUTCOME MEASURES

The four most common outcome measures utilized by chiropractors are the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), the Pain Diagram, the Neck Disability Index (NDI) and the Oswestry Low Back Questionnaire. However, it is important for the chiropractor to also be familiar with the Roland-Morris, the Disability Arm Shoulder Hand (DASH) and the Lower Extremity Function Scale (LEFS). The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) in Ontario suggests the Roland-Morris for programs of care focusing on acute lower back pain. The DASH is a self-reported questionnaire that reveals activity limitations in patients with upper extremity injuries. The LEFS evaluates activity limitations in the case of lower extremity injuries.

THE ASSESSMENT OF DISABILITY

Our patients frequently ask for a note to return to work or expect us to fill in a disability certificate for their insurer or other payer. Information about the essential tasks of the person’s job and their activities of daily living can be practically obtained through the patient history. An opinion on disability is preceded by an analysis of the patient’s impairment in comparison to the physical demands placed upon them. You might also need to determine any medical restrictions that a patient’s employer needs to know for there to be a safe and timely return to work.

THE REHAB PROGRAM

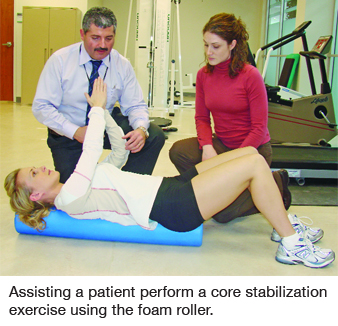

In rehab planning, consider your patient’s impairment(s), activity limitations, disability status and goals. Identify the muscles that are hypertonic/ tight, inhibited/weak as well as any muscular imbalances. Use some degree of functional testing and outcome measures. Start off by giving simple stretches – but not too many at one time – and some instruction on cardiovascular exercise. Be progressive with strengthening, i.e., isometric, isokinetic and isotonic. Add proprioceptive/ balance type, stabilization, postural sparing exercises and sport-specific or work-specific exercises. Knowing a variety of exercises makes it easy to make modifications for particular circumstances.

The exercises should be fun so that compliance is ensured. Provide pictures and written instructions. References for exercise prescription include Liebenson’s 2nd Edition on Rehabilitation of the Spine, an excellent practitioner’s manual containing the latest evidence on lumbar spine stability, outcome measures, yellow flags, quantification of physical performance, exercise prescription and much more. An accompanying DVD contains certain assessment methods as well as exercises that can be demonstrated to patients.

A new chiropractic graduate is qualified to provide a degree of rehabilitation in practice. Further upgrading in rehabilitation and functional testing is available through additional courses and workshops but those seeking a more comprehensive approach might pursue the specialty college fellowship program.

An open space in your clinic is the first requirement. You can purchase exercise equipment such as mats, weights, bands, bikes, therapy balls, a universal gym, and educational materials. Adding rehabilitation services, which require patient supervision, will impact your chiropractic operation.

Integrating rehabilitation into your practice will provide you with experience and, possibly, increased exposure

to multidisciplinary environments such as private rehabilitation clinics and hospitals and with employers, insurers and lawyers.

Other individual providers in today’s competitive field of rehabilitation range from physiotherapists, physiatrists, massage therapists, kinesiologists, and personal trainers, to occupational therapists, and there are also the large rehabilitation networks.

In embracing rehabilitation, the chiropractic profession expands its continuum of care from a passive to an active mode. Patients benefit, appreciating the calibre of education and training that we bring so that their function might be restored, facilitating reintegration into their pre-injury lifestyle.

Print this page